Minority Mental Health Care Access

Can We Level the Field for BIPOC Americans?

We’re therapists. We believe that the healing work we do helps people live fuller, more authentic lives. We want to help ease suffering and resolve trauma, but the desire to help may not be enough in the face of inequities in our mental health care system.

We're presenting this article to give you the facts about disparities in access to mental health care and to offer suggestions about what each of us can do.

- First, we’ll present the numbers that illustrate what mental health disparity looks like in our country.

- Second, we’ll offer information to help you recognize the contributing causes.

- Finally, we’ll provide resources to help you frame the challenges facing our field as we strive for equal access to good quality mental health care for everyone.

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, nearly one in five U.S. adults live with a mental illness. That’s 52.9 million people in 2020. Rates of mental illnesses among Black Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) are similar to those of Whites. But only 17% of BIPOC Americans who need mental health care receive any; while 33% of Whites are able to access the mental health care they need.

The Facts Paint the Picture

According to the office of the US Surgeon General, African Americans and other racial and ethnic minorities generally receive poorer quality care and lack access to culturally competent care. Because of this disparity in care, mental health disorders are more likely to last longer and result in more significant disability for BIPOC Americans.

What Do the Disparities Look Like?

The American Psychiatric Association gathered data from a number of government and other trusted sources to compile this list of disparities

- Compared with Whites, BIPOC Americans with any mental illness receive lower rates of mental health services including prescriptions, medications and outpatient services. They are less likely to receive guideline-consistent care and less frequently included in research.

- Compared with Whites with the same symptoms, BIPOC Americans are more frequently diagnosed with schizophrenia and less frequently diagnosed with mood disorders.

- Physician-patient communication differs between African Americans and other minorities and Whites. One study found that physicians were 23% more verbally dominant with BIPOC patients and engaged in 33% less patient-centered communication with those patients than with white patients.

- BIPOC Americans with mental health conditions, particularly schizophrenia, bipolar disorders and other psychoses are more likely to be incarcerated than people of other races.

- Black American adults are 20% more likely than Whites to experience serious mental health problems, such as major depressive disorder or generalized anxiety disorder.

- According to a 2019 study, African Americans have the highest lifetime prevalence of PTSD (8.7%) compared to their white (7.4%), Latino (7%) and Asian (4%) counterparts.

The Disparities for BIPOC Children and Adolescents Have Life-Long Impacts

We’ve captured just some of the statistics that point to significant health inequities for BIPOC children and adolescents. These are more than numbers; they are a warning—pointing to lifelong differences in the average length of life, quality of life, rates of disability, severity of illness and access to treatment for BIPOC Americans.

- Psychiatric disorders in childhood have been linked to negative outcomes, including poor social mobility and reduced social capital.

- In the BIPOC community, childhood depression has been associated with increased welfare dependence and unemployment.

- Psychiatric and behavioral problems among BIPOC youth often result in school punishment or incarceration, but rarely mental health care.

- Black and Latinx children were about 14% less likely than White youth to receive treatment for their depression.

- Approximately 50% to 75% of youth in the juvenile justice system meet the criteria for a mental health disorder.

- Over 25% of Black youth exposed to violence have proven to be at high risk for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

- In 2018, a study found that the suicide rate of Black children 5 to 12 was nearly twice that of White children of the same age.

- In 2019, suicide was the second leading cause of death for Black Americans, ages 15 to 24; The leading cause for Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders ages 15-24.

- Self-reported suicide attempts rose nearly 80% among BIPOC adolescents from 1991 to 2019, while suicide attempts did not change significantly among Whites and Hispanics.

- Adolescents of color who identify as LGBTQ may be especially at risk of a suicide attempt.

- BIPOC children and adolescents who died by suicide were more likely than White youths to have experienced a crisis during the two weeks before they died.

You can find the sources for these and many more statistics here.

What Contributes to Mental Health Disparities?

According to SAMHSA, “service cost or lack of insurance coverage was the most frequently cited reason for not using mental health services across all racial/ethnic groups.” BIPOC Americans have an additional set of factors that feed these disparities. According to a 2021 HHS report, “persistent systemic social inequities and discrimination” worsen stress and associated mental health concerns for BIPOC Americans.

- Approximately 11% of African Americans are not covered by health insurance, compared with about 7% for non-Hispanic whites.

- Poverty is an absolute barrier to mental health care and BIPOC Americans living below the federal poverty guidelines are 2x as likely to report serious psychological stress as those living 2x above the poverty level.

- Homelessness presents huge obstacles to accessing mental health care. The BIPOC community comprises approximately 40% of the homeless population, 50% of the prison population, and 45% of children in the foster care system.

- Compared with Whites, BIPOC Americans are more likely to use emergency rooms or primary care rather than a mental health specialist.

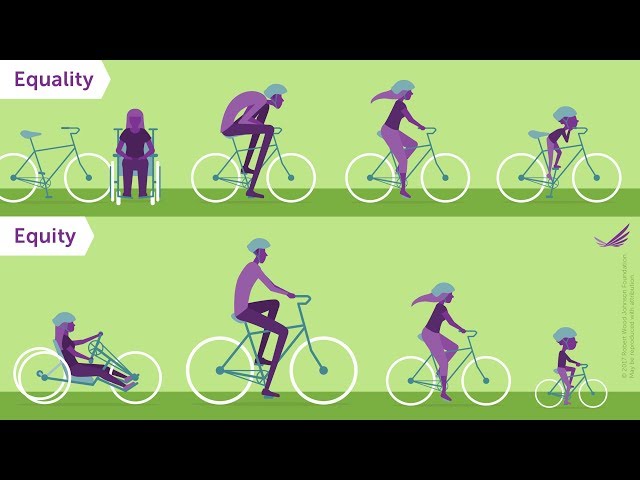

Can We Achieve Equity in Mental Health Care Access?

Once we understand the kinds of barriers BIPOC Americans face, we can start to consider what might level the field. That's a long term project and it requires our understanding of the difference between Equity and Equality. The video From the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation below does a clear and compelling job of explaining. Watch it now.